NEPA's Role in Breaking Baseball's Color Barriers

Wilkes-Barre and Scranton served prominently during the integration of professional baseball.

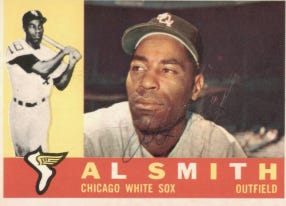

Al Smith had no business being that good, but there he was: the 19-year-old starting shortstop for the Negro American League Champion Cleveland Buckeyes. A teenager should scuffle. They should be seen and not heard.

Well, his fielding was seen, and his bat was loud. It lashed a league-leading 27 doubles, plus 13 triples. And in Game 2 of the Negro League World Series, he roped a game-winning walkoff single.

The Cleveland Indians had just integrated the American League with Larry Doby. They saw enough promise that they wanted to add more talent. Smith was getting attention — and he was young. A player to build around.

Al Smith was one of the first players they signed, and they quickly assigned him to Wilkes-Barre in the Eastern League.

That meant the Diamond City would be the first team in the league to integrate. And all the stress would be plopped onto Smith’s strong, but 20-year-old, shoulders.

Smith would play 68 memorable games in Wilkes-Barre that season, but he wasn’t alone in breaking barriers while in NEPA. The region would be part of an ill-fated push to integrate the Red Sox, and several future Cleveland stars would play in Wilkes-Barre.

Smith crushed the league in ’48, hitting .316/.425/.433. He’d hit 8 triples, 8 doubles, and swipe 5 bases in that short span.

The next season, he was just as dominant, scoring 112 runs, hitting 27 doubles, slashing 17 triples, and blasting 12 homers.

It was the talent and dedication that would lead him to All Star teams in 1955 and 1960.

That 1949 season also featured what might have been the best pro season by any player in the city’s history. Harry Simpson scored 125 runs, drove in 120 and hit .306/.401/.596 as a 23-year-old.

The following year’s roster included Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton. He hit .304/.358/.464 in his final professional season.

Clifton would go onto greater fame on the hardwood as a member of the Harlem Globetrotters and New York Knicks.

An NBA All Star in 1957, he scored 10 points and 8.2 rebounds per game over his 544-game career.

He was the first Black man to sign a contract with an NBA team and was inducted into the league’s Hall of Fame in 2014.

Scranton had its own memorable — if sad — brush with integration.

The Red Sox were infamously the last team to integrate, even missing out on Willie Mays, whom they tried out before the Giants signed him.

Piper Davis was a dominant player and manager in the Negro Leagues. Branch Rickey considered him when he signed Jackie Robinson in 1946. Rickey worried that Davis was too old. The St. Louis Browns signed Davis, but never promoted him to the Major Leagues.

The Red Sox signed Davis in 1950 and assigned him to Scranton. They paid him $7,500 with the contract to double if he was still on the roster by a specified date.

It wasn’t an easy time. During his first game, it took a long time for another player to join him in a game of catch during warmups. Finally, Dale Lynch, who played four years in Wilkes-Barre and Scranton, join him in a game.

Fifteen games into the season, Davis led the team in batting, home runs, and runs batted in.

And the Red Sox cut him from Scranton’s roster.

The moment haunted Davis for the rest of his life.

In 1987, Davis told author Allan Berra:

“That's the only thing that happened to me in baseball that I had bad dreams about later. Sometimes late at night I'd just lie in bed and play that whole scene over and over in my head, trying to make it come out different than it did.”

The Red Sox’ motivations have been debated for decades. Accusations of racism have dogged the franchise’s front office during 1950s and 1960s.

However, Davis himself thought Red Sox first baseman Walt Dropo stood in his way. Dropo was on his way to winning Rookie of the Year that year while setting a record for rookie runs batted in with 144.

One of Willie Mays’ biographers has a different idea. He argued that Davis, who was Mays’ manager in the Negro Leagues, was signed in hopes of getting Mays. When Mays signed with the Giants, Davis was no longer needed.

If that was the case, it’s incredibly short-sighted, even if Davis was 32.

The Baltimore Afro-American’s Sam Lacy commented on the incident.

“They knew how old he was when they plucked him from his manager’s job with the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League … he didn’t suddenly sprout whiskers …”

The Kansas City Call crushed the move, pointing out that Scranton was in last place.

Davis had complex memories of Scranton.

He faced racist taunts during games.

He recalled one fan shouting a slur at him during an at-bat. When Davis homered, other fans came to his defense, according to Davis’ SABR bio.

Davis wasn’t the only Negro League star to play in Scranton, particularly when the franchise became a part of the St. Louis Browns organization.

In 1950, several former Negro League stars shone for The Electric City.

The best was probably Leon Day, who had already built a Hall of Fame career. In Scranton, a then-35-year-old went 13-9 with four complete games.