Antonin Scalia was going off, as usual, on one of the many topics that got his robes twisted in bunches. Affirmative Action. It wasn’t good policy in his view. Who could have ever benefited from it, he scoffed.

“We’ll, Nino,” piped up an elegant voice. A voice forged on the windswept Arizona farmland. “How do you think I got here?”

With that, the curmudgeonly jurist was quiet and the F.W.O.S.C. had the floor.

For much of the last 40 years, the F.W.O.S.C. has had the floor.

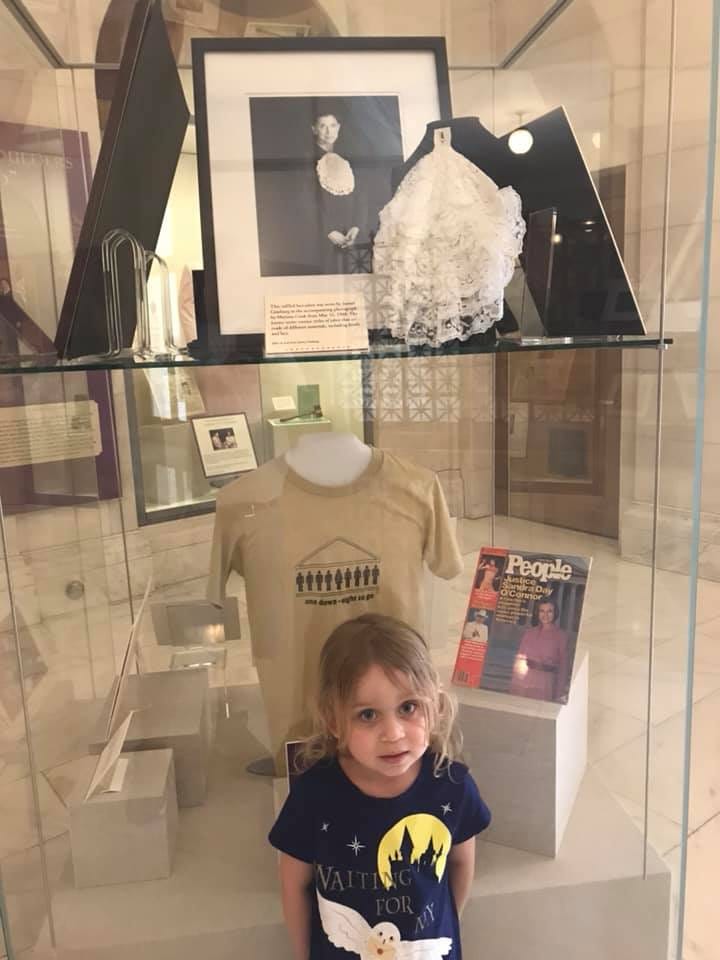

No woman in our nation’s history has been more influential than Sandra Day O’Connor.

Not Abigail Adams or Susan B. Anthony. Not Harriet Tubman or Eleanor Roosevelt. Not Nancy Pelosi or Hillary Clinton. Not Oprah.

O’Connor, the First Woman on the Supreme Court, held the nation’s floor with grace, and verve, not to mention an impeccable resolve and a deep love of civics.

She often did it behind the scenes, holding the court’s center together. Imagine that! A Supreme Court with a center! Well, that was her domain.

But even O’Conner had her faults. What’s refreshing is that unlike so many of today’s leaders, she often owned them, even those faults that damaged the nation.

So, who was the F.W.O.S.C? And how was she so influential?

O’Connor was an Arizona farm girl first. And last.

Her experiences on her father’s Lazy B ranch forged an independent spirit that deeply believed in individualism and fairness.

She would go to school in California, where she would meet, date, and nearly marry future Chief Justice of the United States William Rehnquist.

When she graduated, law school, firms passed her up.

After all, she wasn’t a man.

O’Connor didn’t quit. Soon she would be working in law, then become the first woman ever to be the speaker of a state house.

That’s a hell of a glass ceiling to break. Then she took on the robes.

Being the First Woman on the Supreme Court wasn’t necessarily her goal. She wasn’t really in the business of blazing trails.

Though she would later be overshadowed on the Supreme Court by her partisan colleagues Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsberg, O’Connor was the far more effective justice.

Part of that was her genius at politics - and her colleagues’ political blunders.

It is worth noting that she is the last justice to be named to the court who held an elected position.

In other words, if you were born after 1980, none of the 12 successful SCOTUS nominees in your lifetime have held elected office. That’s been a bad trend for the nation.

O’Connor’s influence came from two approaches.

First, she usually avoided making expansive rulings. When she wrote an opinion, she would limit the outcome to the facts of the case at hand. That meant she didn’t offer breathtaking changes to the law. That technique made her opinions more amenable to the moderate justices of her tenure: Byron White, Anthony Kennedy and David Souter.

While those limited decisions might have kept her from being praised by the partisans on either side, it did allow her to shape national policy in her image in several areas.

Affirmative action was OK in some situations, according to her.

Having experienced sexism in the legislature and the courts, she understood that the day of jubilee on those issues had yet to arrive. Hell, during her first day on the highest court in the land, she opened her mail to find one citizen had mailed her a picture of his, shall we say, constitution.

It didn’t impress her.

So she let affirmative action policies stand in many areas, while restricting it in others.

Abortion might be the nation’s thorniest topic. And O’Connor somehow managed to thread the needle, leaving both sides of the debate elated and disgusted at times.

That’s where her second approach showed her political genius.

O’Connor often avoided announcing to her colleagues where she stood on a case. They had to work for her vote if they wanted a 5-4 majority.

Most people think of courts based on their Chief Justices. The Roberts Court. The Rehnquist Court. The Taft Court.

However, it’s really the swing justices who sway the court’s decisions.

And few justices - if any - held the center for so long. She was basically the swing justice for two decades.

Sometimes, as in Planned Parenthood V. Casey, the side she was expected to join lost her vote and the outcome.

O’Connor had no problem with the state restricting abortions, but the idea that a woman would have to ask her husband for permission? Well, that just didn’t sit right with Justice O’Connor.

So she would write opinions that would capture the other moderate’s votes.

And, until recently, the law of the land on that particular issue fit O’Connor’s vision.

O’Connor’s political decisions didn’t always work out. For the nation or for her.

In 2000, she wanted to retire and spend time with her beloved John.

On election night, she saw Democrat Al Gore was about to win and vented to friends.

A few weeks later, she would join the other four conservative justices in ending the Florida recount and handing George W. Bush the election.

It would become a stain on her legacy, and one she would go on to regret.

O’Connor would finally retire in 2006. Initially, she was going to step down earlier and be replaced by John Roberts, whom she appreciated. However, when then-Chief Rehnquist died, she had to delay her retirement briefly while Roberts took that position. She then was replaced by Samuel Alito, who was a bit truculent, whiny and right-wing for her taste.

However, she had another battle - one she fought with her natural unflagging grace.

O’Connor’s husband, John, had forged his own prestigious legal career when Alzheimer’s struck in the early 2000s. At first, she quietly brought him to court with her.

Eventually, after her retirement, she had to put him into a home. There, she would visit him. It was there John, who couldn’t quite remember Sandra, fell in love with another woman.

The Justice would find him holding hands with her. So she would walk over, sit next to him, and in her quiet strength, hold his other hand.

It’s hard to imagine what that must have been like.

Or to then find out you were also suffering from dementia, as O’Connor did toward the end of her life.

She withdrew from public after serving as president of William and Mary, a decade ago.

It’s almost incomprehensible that someone’s greatest strength, a humble - and often profound - wisdom could become their downfall. It’s too Shakespearean.

But it’s also all too human.

Just like Justice O’Connor.

****

If you’re looking for more on the F.W.O.S.C., check out Evan Thomas’s bio of her or Joan Biskupic’s look at her relationship with Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Her own memoir, about her time on the ranch, is also wonderful as an audiobook that she reads.